Wilkinson's Swords, Part Two by Robert Wilkinson-Latham

Editor’s Note

As with the first article in this series, this instalment seeks to preserve and share the knowledge that Robert Wilkinson-Latham disseminated over many years on the Sword Forum International website. Henry Wilkinson and the Wilkinson Sword Company are still well known for their excellence in producing a variety of bladed weaponry and their swords are sought after by collectors to this day. Presented here is the sum total of many thousands of forum posts, each fully explored alongside any related threads, the information then transcribed and organised into appropriate subheadings. I have edited these notes together to form prose more suited to the medium here, striving to retain as much of the original author’s words and voice as possible while combating the succinct, disjointed nature of forum posts that comprise such sources. Any text that you find set within quotation marks is presented verbatim. I hope these articles will serve as interesting references for my fellow sword collectors and researchers and I am thankful to both SFI and Robert Wilkinson-Latham for kindly giving this important and interesting project their permission and support.

Matthew Forde

Products

Sword and Razor Showroom, Pall Mall, 1900s

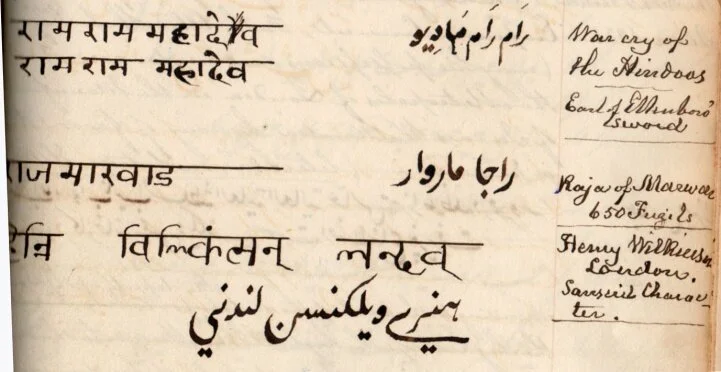

British Army officers, and other customers, could visit the sword showroom at 27–28 Pall Mall and choose their swords “in leisurely surroundings”. Regardless of which sword pattern was bought, Wilkinson only supplied completed swords (including change-over hilts such as those found on some Scottish regulation patterns) and they never sold replacement parts except for scabbards. There were several grades and types of sword on offer and buyers could pay extra to have any of them etched with extra details, such as a company’s name or a regiment’s name, their own initials, or even a message such as in the case of presentation swords. I shall list the grades of sword available below.

Best Proved Sword: Best proved swords had the highest possible standard of finish and were usually completed by hand. Their steel scabbards were supplied with leather linings and German silver mouthpieces. The blades were stamped on the spine with a serial number and recorded, often along with the buyer’s name, in Wilkinson’s blade proving record book.

Buyers of best proved swords could also choose different blade types:

Regulation.

Percy: biconvex and double-edged.

Solid: single-edged and without fullers.

Lozenge: lozenge-shaped in section and double-edged.

Claymore: there was a vogue for these to be used on Royal Navy swords and also Chinese Maritime Customs swords.

Triangular: triangular in section and single-edged.

Paget: a highly curved blade similar to that on the 1796 Pattern Light Cavalry Sabre.

Keyhole, quill or pipe: a pipe-backed blade in vogue before 1846 but occasionally encountered later, too.

Toledo: dumbbell-shaped in section and then double-edged for the final 12 to 16 inches from the point. This shape was fashionable from the 1850s to the 1870s due to the popularity of fencing and skill-at-arms displays, and were mainly found on infantry swords of the period. John Latham’s lecture to the RUSI, The Shape of Sword Blades, delivered in May 1862, mentions the Toledo (or the latchen as it was known amongst the workmen) as the oldest form of thrusting blade.

Best Proved Sword with a Patent Solid Hilt: Also referred to as a patent solid tang, solid hilt and patent tang, this was the most expensive ‘normal’ sword available to buy at Wilkinson and they were made as early as 1854. They offered all the fit and finish of the best proved sword but, in addition, had a tang-width that matched the width of the blade, making for a stronger weapon. They would always be marked with the words Patent Solid Hilt etched into the blade’s ricasso along with the company’s usual markings. If they were supplied to a retailer who also wanted their logo included then that would be applied in addition to the Wilkinson name.

The patent for a full-width tang was established by the sword maker Charles Reeves on the 21st of April, 1853. In adverts and documents he had called it The Registered Sword and Wilkinson initially produced its own under licence—presumably paying a fee to Reeves although there is no mention of royalties in the Wilkinson archives: “so possibly the patent hilt-use was done in friendly co-operation”. In the 1880s, Wilkinson purchased a large percentage of Reeves and with it the by-then defunct patent, renewing it and calling it the Wilkinson Patent Solid Tang when the Reeves sale had been completed in the early 1900s. On the subject of Charles Reeves: there had long been a connection between Wilkinson and Reeves and, in fact, Henry Wilkinson’s proving machine and blade forging was done at Issac Hebberd’s premises in Air Street (with the other work, sword mounting, etching and finishing being done at 27 Pall Mall) [Hebberd was a sword cutler and military ornament maker in Piccadilly until around 1851 when he moved to Fulham]. In 1853, Charles Reeves bought Hebberd and, going from the proof stubs, Wilkinson’s blades continued to be proved there, a least during 1854. It is reasonable to assume that Wilkinson paid Reeves a royalty for the use of his patent and this working relationship laid the foundation for the company to buy a majority share in Reeves in 1883.

The earliest recorded Wilkinson-made sword with a patent solid hilt is number 5002 which was proved on the 1st of January and finished on the 24th of January, 1854.

Common Proved Sword: These have become known by a variety of titles, including trade-blades, outfitters’ quality and retailers’ quality but the company probably referred to them as common proved blades. Although still made to Wilkinson’s high standards, they had less ornate hilts and blades, and were not normally numbered on the spine (and if they were it was usually with the retailer’s own order number rather than Wilkinson’s—as one finds with Hawkes’ swords). This class of product was often used to supply colonial contracts as well as military outfitters and also for individuals who couldn’t afford a best proved sword. Wilkinson had a number of different punches for their common proved swords’ proof marks, and they appear to have been used haphazardly, from at least the 1860s onwards. These marks include:

PROVED over a crown (circa 1880s).

A crown over PROVED (probably as above).

PROVED over a fleur de lys (circa 1860s).

PROVED above a T. (which stood for tested rather than proved, circa 1870).

A crown over a W*.

*This proof disc was used sparingly from the late 1860s to the early 1870s and it has been discovered on sample contract-quality swords made for Siam in 1870 which did not have the double triangle mark but a Mole-style burst of rays instead. The forte was etched with Wilkinson Pall Mall London on the other side.

Sword sticks were sold from the 1870s (or thereabout) until the early 1960s. They came in various stick styles. Also made were officers’ swagger sticks, leather covered and with a concealed blade inside. Lead-cutters came in four sizes, were always single-edged and modelled on the Royal Navy’s 1845 Pattern Cutlass (the first were 1845 Pattern Cutlasses).

No 1: 29 x 1 ¾ inches.

No 2: 31 x 1 ¾ inches.

No 3: 33 x 2 inches.

No 4: 34 x 2 ¼ inches.

Cutlasses were supplied to private yachts—a catalogue from the 1870s refers to the sale of “cannon, rifles, muskets, bayonets, pistols, cutlasses, boarding pikes, tomahawks...and every kind of apparatus and material required.”

“Very few finished orders were not collected but, if so, they were almost certainly of a regulation pattern and so would simply be sold to another officer. In all my years looking at the proof registers, I have only come across a handful where one name has been crossed out and another substituted and even fewer show the ‘return to stock’ inscription.”

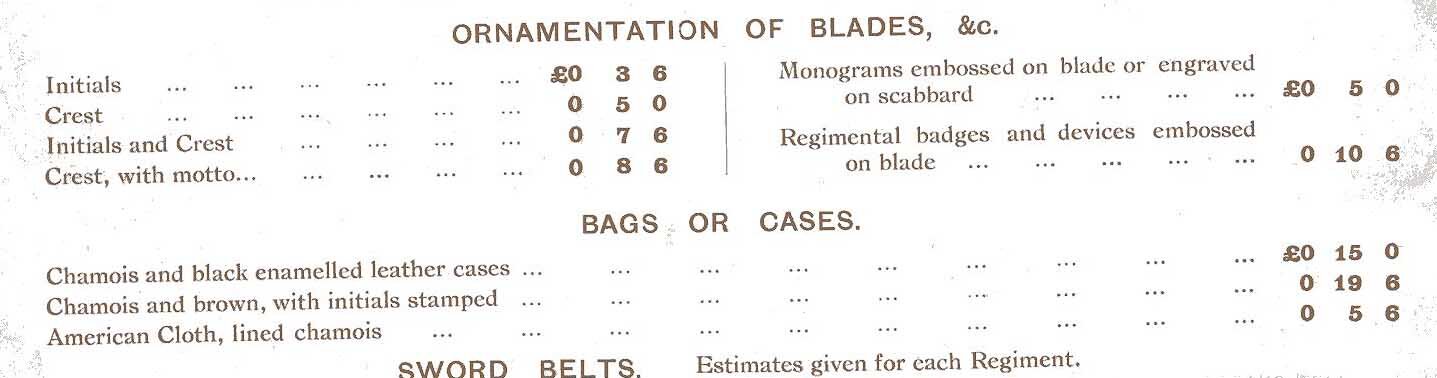

For those interested, here is a list of sword prices from 1902:

Regulation infantry swords were £5-5-0 or £6-10-0 with a patent solid tang.

Rifles swords were £5-5-0 or £7-0-0 with a patent solid tang.

Cameronians and Rifle Brigade swords were £5-15-0 or £7-0-0 with a patent solid tang.

Medical staff swords, with gilded hilts, were £4-4-0.

Royal Engineers swords were £5-5-0.

Guards swords were £7-10-0.

Claymores were £7-15-0.

Royal Artillery swords were £5-17-6 or £7-2-6 with a patent solid tang.

Nickel plating for a sword’s hilt and its dress scabbard incurred an extra cost at £1-2-6. (“I think nickel plating became the norm at the beginning of World War One.”) Leather hilt covers for regulation swords are described in a catalogue (circa 1900) under the heading Foreign Service Equipment. They cost seven shillings and sixpence and Wilkinson would appear to supply them for all pattern swords, if asked.

Of course, Wilkinson also made swords for people outside of the armed forces and one such product commonly found today is the Masonic sword. There is no mention of Masonic swords in any catalogue up to 1926. From leaflets, it would appear that Masonic swords were made from around the late 1920s onwards. Wilkinson made medieval-style swords from the Victorian period onwards for presentation and commemoration purposes and always etched their name on the blade. They did not exactly copy extant medieval designs on purpose to avoid fraud [on the part of future owners indulging in some artificial ageing and trying to pass off such swords as being genuinely medieval]. Two copies of a Roman gladius were made (see Swords in Colour, 1976, plate 5). One was sold and the other sat in the company’s museum. “It certainly disappeared long before the museum closed in 2005 as it does not feature on the disposal, loan or sale lists prepared, nor on the CD of every individual item in the museum at the time, both of which I have. It was not sold at Bonham’s so probably sold in the late 1990s as it was [still] there in 1998. [It had a] steel blade, wooden scabbard and gilt-brass mounts. The grip was, I think, composite.”

Wilkinson made a limited number of commemorative cledds in the 1960s but were never involved with the design of World War One original. The records of that period are very precise when it comes to sword and bayonet production and there is no mention of any ‘specials’ being made. If Wilkinson had been asked to make them they would have required War Office permission to take on extra work as the entire factory output was already devoted to War Office, India Office and Admiralty contracts. The drawings I have are dated to July 1978 and are annotated with “Drawn from a reputed model”. The Wilkinson drawing has the following as blade markings:

URDDAS

DROS

CYMRU

Most, if not all, of the World War One production of government contracts (bayonets, swords, et cetera) and private swords were paid for under the piecework system. I have some piecework cards from World War One but these are easy to operate as they are for 1908 sword parts being finished, polished, and so on, and 1907 Pattern Bayonet parts—the foreman would count up the numbers in the tray at the end of the worker’s shift and sign the card off.

The scimitar or mameluke sword was favoured for presentation to military and naval men for service above and beyond the call of duty. This tradition was upheld even after the Falklands War in 1982 and the company often termed them ‘fancy scimitars’. The choice of grip material included ivory, walnut and others.

Henry Wilkinson displayed some of his products at the Great Exhibition of 1851, listed in the official catalogue as being ‘Wilkinson and Son, 27 Pall Mall’ and entered under class VIII: manufacturers. He took along examples of all the regulation swords in use in the British Army and Royal Navy at the time, and “as originally submitted to the Commander-in-Chief and to the Lords Commissioners of the Admiralty, by the exhibitor, and approved and adopted by general orders”. These were:

(a.) Regulation infantry sword, as by general order dated March 10, 1845.

(b.) Regulation sword for Royal Engineers.

(c.) Light cavalry and Royal Artillery sword.

(d.) Heavy cavalry sword.

(e.) 1st Life Guards sword.

(f.) 2nd Life Guards sword.

(g.) Royal Horse Guards (Blues) sword.

(h.) Regulation highland claymore.

(i.) General officer’s cimeter.

(k.) Admiral’s dress cimeter.

(l.) Regulation sword for Royal Navy, as per Admiralty order, dated November 23, 1847.

7. A sword worn by some of the irregular cavalry in India: the hilt of steel, electro-plated with silver; the scabbard of German silver.

8. A coat of chainmail, of tempered steel electro-plated with silver; also a pair of gauntlets, bridle, et cetera, of the same material, as worn by some of the irregular cavalry in India.

9. Two helmets covered with electro-plated steel chainmail, in gold and silver, to be used without a plume.

10. A highland claymore copied from an old one by Andrea Ferrara.

11. Regulation and other sword belts.

12. A highland dirk as designed and manufactured by the exhibitor, for Her Majesty’s 74th Highlanders.

13. A series of illustrations showing the different stages of the manufacture of sword blades.

Wilkinson took over Pinder in 1906 to produce hunting knives, penknives and cutlery. They adapted Pinder’s elongated triangular mark and inserted the name Wilkinson, also using it on other items such some razors, corn cutters and so on.

Miscellaneous Notes

Royal Artillery Swords

Wilkinson blade rubs show that the Royal Artillery officers used the regulation 1845 Pattern Infantry Officers’ Sabre from 1846 to 1852. Dress regulations state, regarding the sword for the Royal Artillery that it was to be a: “half basket, steel hilt, with 2 fluted bards on the outside: black fishskin grip bound with silver wire. Slightly curved blade, 35 ½ inches long and 1 ¼ inches wide, grooved and spear-pointed.” This Pattern, numbered 336, was sealed on the 26th of October, 1863.

1914

Cavalry Swords

The government’s specifications give us the following information:

1853 Pattern (referred to as the “Old 3 Bar Pattern”): 2lb 1 ½ oz to 1 oz tolerance. (From the two specifications from different dates that I have, and the Table of Small Arms from 1891, there appear to be three different weights for this sword!

1864 Pattern: 2lb 6 0z to 2lb 8 oz.

Conversions from the 1853 Pattern to the 1864 Pattern: 2lb 2 oz.

1882 Pattern Short (converted from the 1864 Pattern): 2lb 1 ½ oz with 1 oz of toleration each way.

Here is an example of the operations required to make an 1885 Pattern Sword and Scabbard, for which the government paid the firm Robert Mole under £1-2-0:

May 1886.

Blade: 32 operations.

Scabbard: 30 operations.

Mouthpiece with sputcheon [the metal lining at the mouth of the scabbard]: 32 operations.

Linings for scabbard: 11 operations

Handstop: 16 operations.

Riveting: 7 operations.

Scales: 4 operations.

Drag for scabbard: 6 operations.

Loops (scabbard rings): 4 operations.

Guard: 5 operations.

Leather grips: 7 operations.

Mounting the complete sword: 10 operations.

Leather buff: 2 operations.

Making a total of 156 operations. Not ‘out of the woods’, yet: there was testing and inspection still to come. Blades (after grinding) were weighed and if they were lighter than the minimum allowed in the specification then they were rejected. If over, they were sent back to the grinders. If okay, the blades underwent the strike test and the bend test. After that, all parts of the blade and tang were gauged and the hilt was gauged and weighed. The hilts were fitted to the blade and the whole unit then weighed: if underweight it was rejected, if over it was sent for extra work. The complete sword was then tested and gauged for balance and the scabbard was tested for weight, gauged and also for interchangeability. For the money, it was no wonder at this time there was only Mole [Robert Mole and Sons, a Birmingham-based sword cutler] prepared to do it!

The gauging tolerances were:

Length from point to shoulder: 34 ½ ins.

Shoulder to end of tang: 5 3/8ins.

Weight of polished blade: 1lb 6 ½ oz to 1lb 7 ½ oz.

Weight of polished hilt: 8 oz to 9 oz.

Sword complete: 2lb 5 oz to 2lb 7 oz.

Balance: 5 ins to 5 5/8 ins from hilt.

Scabbard: metal thickness: 04ins or No. 19 BWG.

Weight of wood lining not to exceed 4 oz.

Scabbard complete: 1 lb 13 ½ oz to 1lb 15 ½ oz (later reduced to 1lb7 ½ oz to 1lb 9 ½ oz).

It must have been a maddening for Mole to make this sword because the Chief Inspector of Small Arms, Enfield kept changing the specifications and inspection standards. In my files I have the following dated specifications for the 1885 and all differ.

3/12/1888

7/3/1889

27/4/1889

9/11/1889

14/11/1889

20/11/1889

4/1/1890

Concerning the 1908 Pattern Cavalry Troopers’ Sword, in 1910 the sword knot’s slot was increased in length by half an inch, in 1911 the top part of the blade near hilt was serrated to better hold the washer and in 1912 that serration was discontinued with the washer being held in place with a pin instead in which case the sword becomes a ‘Mark I’. Hilts were certainly painted, in some cases as required by contract at the factory. Paperwork exists proving this. Even if the guard was leather-covered, all of the parts would have been put through inspection. There are incidents in the Middle East where troopers carried Pattern 1908 Sword with leather-covered hilts.

Concerning the 1912 Pattern Cavalry Officers’ Sword, specifications state that the grip should be as follows: “The length of the grip: variation allowed to suit the size of the hand.”

Infantry Swords

In what is probably a reply to a journalist, found in the Wilkinson copy letter book and dated to February 1896, tells us something of the company’s opinion of some of its Teutonic rivals:

“Nearly 90% of Volunteer officer’s swords are German or are German blades. These swords give a far bigger profit to the outfitter or dealer who supplies them. Many of these blades have our style of proof mark and yet they have not undergone the strict testing we confer on our blades or any testing whatsoever. Other English sword makers also test their blades severely.”

On the 1897 Pattern Infantry Officers’ Sword’s ‘Sam Browne’ scabbard, in the original manufacture, the chape is glued to the wooden body and then the body’s covering is sewn on and over the sides of the chape.

“As a youth at Pall Mall, I was dressed down for trying to sell a Rifles pattern sword to an officer in the Somerset Light Infantry! With the help of an older hand, Jimmy Naughton, (he had been at Pall Mall since being demobbed in 1920 having spent the War as batman to HB Randolph (later a senior director) and was given a job at Wilkinson in 1920) I was extracted from this ‘howler’!”

Royal Engineers Swords

I have looked through the surviving blade rubbings for the period and there are no Royal Engineers blade-etch rubbings until the 1857 period and onwards. As for their sword knots:

1857: gold braid and acorn.

1861: gold cord and acorn.

1874: red Russia leather and gold acorn.

1883: gold cord and acorn.

(This is from the company’s regimental ledger regarding sword types, belts, badges and sword knots from 1860s onwards 1870.)

Royal Navy Swords

If a number is stamped onto the hilt [of an 1846 Pattern Officers’ Sabre] it is possible a Royal Naval College drill sword. The College has a large stock of these for teaching Cadets the sword drill.

Royal Air Force Swords

The first RAF swords were manufactured on the 4th of April 1920. These two swords were Sword 58408, made for Vice Air Marshal EL Ellington and Sword 58409, made for Air Marshal Sir H Trenchard. This sword design was then adopted but it appears that it was not officially sealed as a pattern until early 1925.

Lances

“I remember, in the late 1960s, walking from Wilkinson’s in Pall Mall to Hyde Park barracks to deliver three lances to the Household Cavalry—couldn’t do it today, I should think, without attracting a SWAT team!”

The specifications for the lances stipulate 7 differently sized heads and 4 differently sized shoes. (This refers to the internal diameter of the part fitting the stave because of the differing thicknesses of bamboo.) The specification also states the following about the staves:

“To be of solid bamboo or, if hollow, the hole in the centre is not to exceed 0.5ins in diameter. The canes should be cut when the sap is down and carefully straightened over a fire, great care being taken not to burn the skin in the process. Slight natural blemishes on the skin, such as black marks or dots or marks of rubbing die to contact with culm during growth, will not be objected to. ‘Patta’ scars (due to the removal of side branches) at the butt (or shoe) end, behind the point of balance, will also be allowed.”

Foreign Buyers

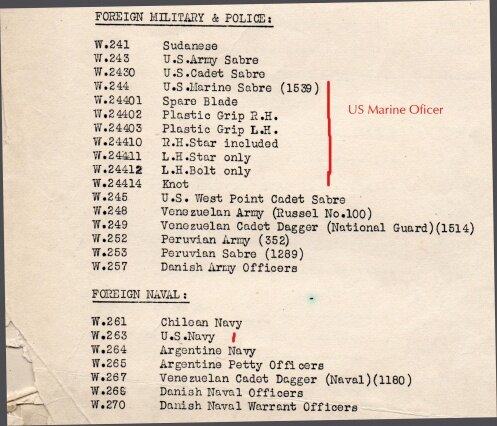

Being a famous and well-respected manufacturer, Wilkinson also made swords for individuals and markets overseas. Between 1947 and the late 1950s, the company made a number of US Navy and US Marines swords (one must remember that after World War Two many of the Solingen-based sword businesses ceased to exist). They also supplied a large number US swords via the Russell Uniform Company of 1600 Broadway, New York, and sold swords to South America which, pre-1939, had been the market of the Solingen-based makers.

A lot of the ex-British Empire and new Commonwealth countries, on being given their independence, ordered swords of British patterns from Wilkinson but with their own crests and so on in place of British details. Malawi ordered a large number of swords from Wilkinson in the 1960s, for instance. After the first orders, some countries bought from WKC instead. A few overseas contracts:

Brunei

Bahamas

Barbados

Singapore

Gold Coast

Royal Hong Kong Police

New Zealand

Zambia

Kenya

In closing, Robert Wilkinson-Latham has authored many books which will be of interest to those who wish to widen their knowledge of historical weaponry, including:

British Cut and Thrust Weapons

Discovering British Military Badges and Buttons

Wilkinson Razors: Straight and Safety 1855 to 2003

If this free article was useful then please consider supporting me on Patreon. By adding your support you gain access to a growing archive of useful articles, in-depth resources and advice, personal help with identifications and restorations, and, as I’m slowly liquidating my collection, early access to new sales. You can help out from as little as £1 (or $1) and everything helps. Thank you for your consideration.